[ad_1]

Hope and Restoration: Saving the Whitebark Pine

[contemplative music builds]

DAN TYERS, USDA FOREST SERVICE: The proof is plentiful and irrefutable that persons are drawn to wildlands. … There’s one thing that resonates within the human soul, in our human situation. And …there’s a explicit resonance … that comes from having white bark pine forests current. It’s distinctive inside a panorama that’s distinctive. It has a way of timelessness since you are strolling by way of a forest of bushes which are a whole bunch of years previous. And what they provide on the panorama can’t be replicated. It might’t be duplicated in a brief time frame…in a tradition that appears … to gravitate to the fast, there’s a longevity, a permanence that you just discover in white bark pine forests that … even when we are able to’t absolutely categorical it – attracts us in.

[Text on screen: Hope and Restoration: Saving the Whitebark Pine]

ELIZABETH PANSING, AMERICAN FORESTS: The factor that I like and admire essentially the most about whitebark pine is … its tenacity. You see this factor rising on essentially the most wonderful ridge tops and at tree line and in these environments the place no different tree can exist.

MIKE DURGLO, CONFEDERATED SALISH & KOOTENAI TRIBES: We’ve been working … working with whitebark pine for a number of years now and I consider it our individuals. Our individuals have survived. Our persons are resilient.

TRACY STONE-MANNING, BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT: There’s one thing actually magical about being in a very high-elevation place that’s actually windy and actually inhospital … and to see these big lovely bushes thriving.

DOUG SMITH, YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK: Whitebark pine is nearly completely a high-elevation tree inside its total vary… they’re the craggy, gnarled bushes that you just see at timberline. They’re that high layer to the forest within the mountains, all the way in which to the Sierras and Cascades and north into Alberta and British Columbia.

ELIZABETH PANSING: … In case you are going mountain climbing at excessive elevations, you’ve most likely handed a whitebark within the western United States and never identified it … if you’re going backcountry snowboarding or should you’re at lots of the ski resorts within the western United States, you’ve most likely skied previous a whitebark and never identified it.

DIANA TOMBACK, WHITEBARK PINE ECOSYSTEM FOUNDATION: The place whitebark pine grows, its canopies…redistribute snow…the shade from their crowns will protect that snow nicely into the summer season.

BOB KEANE, USDA FOREST SERVICE: These forests truly stabilize the snowpack, permitting the snow to soften slower and supply prime quality water for longer intervals in the course of the summer season.

LIZ DAVY, USDA FOREST SERVICE: On this space … numerous people downstream depend on that snowmelt for his or her irrigation water. For his or her culinary water. To replenish the water within the water desk.

MELISSA JENKINS, USDA FOREST SERVICE: White bark pine has so many advantages… and I’m positive there’s rather a lot we don’t even perceive… However most likely an important ecosystem service that white bark offers is a wildlife meals supply. A white bark cone is about 4 or 5 inches lengthy. They’re darkish purplish brown, sort of colour. And they’re very sappy. However the magic is what’s contained in the cone…

BOB KEANE: Whitebark produces these unbelievably giant seeds, the most important seed of any tree that we have now within the Northern Rockies.

DOUG SMITH: As a result of their cones are giant with an enormous nut numerous animals depend on them … and the grizzly bears find it irresistible.

DAN TYERS: They’re attempting to placed on fats for going into the den for a Winter interval. They should achieve as a lot weight as doable and the white bark pine gives them a big return for the vitality expended to obtain it. Andwe have sufficient knowledge after a few years of analysis to know that they’re inexorably tied to the whitebark pine.

DOUG SMITH: You’re within the midst of a whitebark forest right here. When it’s whitebark yr this can be a wildlife hub … So, this can be a actual essential space for bears, for crimson squirrels however the nutcrackers are arguably essentially the most spectacular.

MELISSA JENKINS: I believe that essentially the most fascinating factor about whitebark that basically catches individuals’s consideration …is that undeniable fact that the tree couldn’t exist with out this chook that vegetation its seeds.

DOUG SMITH: Virtually all of the whitebark pine copy up and down the Rocky Mountain chain is because of nutcrackers caching the seeds. So, this forest actually will depend on the chook.

DIANA TOMBACK: A nutcracker will come alongside and take away the seeds from the cone after which they bury small clusters of seeds just about in every single place within the excessive mountain surroundings.

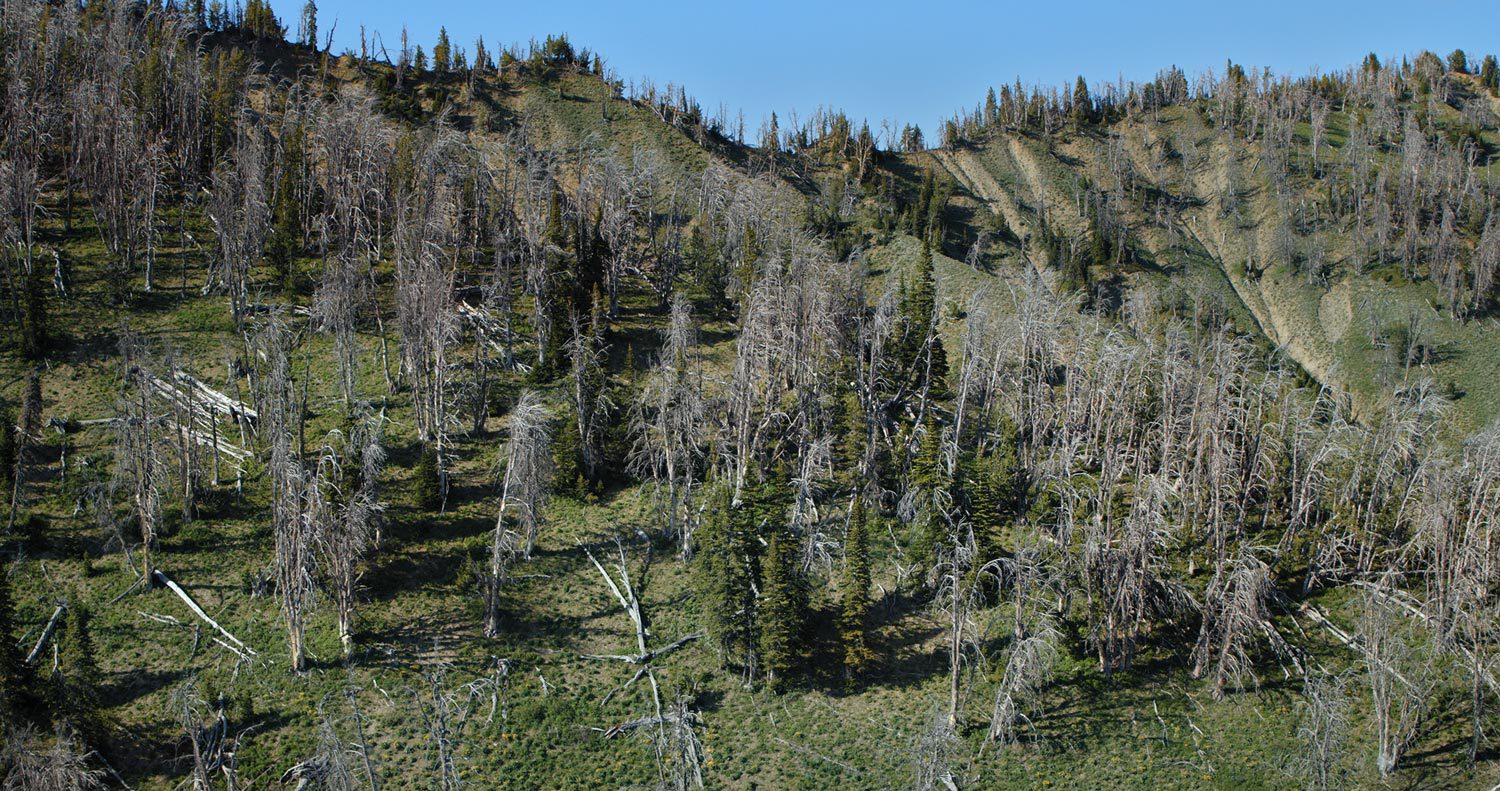

DOUG SMITH: They stash these seeds, generally as much as tens of 1000’s in caches, and nobody can consider that they will recuperate these items, however they do! …They don’t get all of them although. And so, a few of these caches develop into whitebark pine and most of whitebark pine is established that method. And so, the 2 are intertwined. So, it’s a very essential relationship, and it’s beginning to crumble. It’s falling aside as a result of the whitebarks are dying for a number of causes, and it’s exemplified right here. The whole lot I look out and see that’s lifeless is whitebark.

BOB KEANE: For the reason that begin of my profession, the decline of white bark pine is simply breathtaking… In areas we’ve misplaced over 90 to 95 p.c of those bushes.

LIZ DAVY: I started to see complete total higher watersheds die. It was heartbreaking to see that.

ELIZABETH PANSING: You go on the market and it’s actually arduous to discover a wholesome tree on the panorama. It’s miserable. It’s every thing from these little, tiny seedlings which are lower than a foot tall all the way in which as much as the most important bushes on the panorama and each single one among them, just about, has white pine blister rust.

ERIC SPRAGUE, AMERICAN FORESTS: Whitebark pine is dealing with extinction primarily due to white pine blister rust. White pine blister rust is a non-native fungus that infects a tree by way of its needles and slowly creates these cankers that then lower off the circulate of vitamins and water, killing limbs. Over time that spreads and can kill all the tree.

DIANA TOMBACK: This illness has been spreading by way of whitebark pine for almost a century. That is the principle existential risk to whitebark pine.

WALTER WHETJI, RICKETTS CONSERVATION FOUNDATION: I believe should you look again on a few of the historical past of illnesses like this, pathogens which have gone by way of North America, the traditional case is chestnut blight which got here into the U.S. within the late 1800s. And forty years later there have been no American Chestnut left within the forest.

DIANA TOMBACK: If we fail to do something for whitebark pine … we’re going to find yourself with many areas of our excessive mountain areas with out it and we’d lose the ecosystem providers, the wildlife meals, the habitat safety, the watershed safety. Will probably be very obvious that some cataclysm affected our Western forests mightily on a big scale.

JAKE BAKER, USDA FOREST SERVICE: (I don’t assume I want it.) So, as we’re coming by way of right here we’re searching for bushes that we all know to be genetically immune to blister rust. So, these are those we’re going to be caging in right this moment.

DIANA TOMBACK:We have now no remedy for white pine blister rust and … the one recourse we have now is to search for the small variety of people in every inhabitants that appears to have pure genetic resistance. These people are the inspiration of restoring whitebark pine.

JAKE BAKER: These cones might be shipped to the Coeur d’Alene nursery in Idaho and ultimately used to develop seedlings within the nursery.

ARAM ERAMIAN, USDA FOREST SERVICE: The seedlings we’re rising have some degree of resistance to blister rust.On common, we’re rising about 150,000 seedlings per yr… 150,000 one-year-old seedlings, 150,000 two-year-old seedlings.

ERIKA WILLIAMS, USDA FOREST SERVICE: Once we plant bushes the very first thing is we actually search for a wonderful planting location. We’re searching for, like, a log that’s down or possibly a stump; one thing that’s going to offer shade and maintain some moisture and provides it the perfect life and the perfect begin that it could have.

ARAM ERAMIAN: It’s very gratifying to exit and see these seedlings on the panorama… it is extremely humbling I’ll say that we’re having such an influence. And within the particular case, the whitebark pine the place this can be a threatened species, we’re in a position to recreate it and put it again on web site.

MELISSA JENKINS: I’ve numerous hope for the way forward for whitebark pine as a result of I see the fervour within the people who find themselves working to revive it… They’re doing the analysis … planting bushes, accumulating cones, … rising all of the seedlings… and I have a look at all these marvelous, passionate, dedicated individuals. And I – can’t assist however have hope.

DIANA TOMBACK:We have now lots of people that care in regards to the destiny of this tree … However we’re practical as a result of we’ve moved an inch and we all know that we’ve acquired a mile to go.

ELIZABETH PANSING: I’m extremely optimistic about the way forward for whitebark. I’m extremely unhappy about what the panorama appears like at the moment, however I can’t think about taking a look at this because the demise knells. It’s not.

LIZ DAVEY: Restoration is completely doable. We’ve carried out it. We’re doing it. And we’ll proceed to do it. I would like to have the ability to depart one thing for the following era in order that they will take part and see what I’m seeing and expertise what I expertise. Once you’re up at that prime elevation, and also you’re sitting in a whitebark pine stand, and the Clark’s Nutcrackers are flying round, it’s simply … it’s magical. And I shouldn’t be the one one who will get to expertise that.

MIKE DURGLO: You gotta assume, like, you already know, this isn’t only for me. It’s for the long run generations. The forestry program for the primary time in our historical past planted 2,000 bushes. I gained’t see these bushes mature. However our grandchildren and our kids our going to see these bushes mature. And that’s, to me, what it’s all about.

DAVID LYTLE, USDA FOREST SERVICE: About 90 p.c of whitebark pine happens on public lands in america. So it’s critically essential that we as public land administration land businesses are actively concerned in whitebark pine conservation.

TRACY STONE-MANNING: I believe the duty to revive whitebark Pine rests with us all. Irrespective of the place the pine develop all of us have an obligation to make it possible for this species, which is simply so vital for prime elevation habitat, doesn’t wink out on our watch.

MELISSA JENKINS: The extra that I’ve labored with whitebark, the extra that I’ve hope, as a result of I perceive now that there are issues, we are able to do about it. We have now a plan ahead. We all know easy methods to restore the species. Now we want the assets to do this. One among my favourite quotes …. It goes, “The true that means life is to plant bushes below whose shade you don’t count on to sit down.”

[music resolves]

[nutcracker and chickadee calls]

[wind noise]]

Finish of Transcript

From the Autumn 2022 challenge of Residing Chook journal. Subscribe now.

Printed September 2022; up to date December 2022 to point the whitebark pine’s official itemizing as Threatened below the Endangered Species Act.

Some pairings are so iconic that one will not be full with out the opposite: Macaroni and cheese. Abbott and Costello. Peanut butter and jelly. Within the northern Rockies and Sierra Nevadas, that duo is the whitebark pine (Pinus albicaulis) and Clark’s Nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana).

The pine produces giant, energy-rich seeds that the nutcracker caches by the 1000’s, burying them within the soil or gravel of mountain slopes as a stashed meals provide to get the birds by way of the lengthy, frigid winters. However the seeds that aren’t retrieved germinate the place they’re buried—rising into the following era of whitebark pines.

In some high-alpine forests of the West, just about each whitebark pine on the panorama sprouted from seeds planted by a nutcracker. Up to now few a long time, the twin risk of a fungal illness and a forest pest have worn out huge areas of whitebark pines. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that over half of all whitebark pines have died, with a lot of that destruction taking place within the final 20 years. With out motion, says Robert Keane, an ecologist on the U.S. Forest Service Rocky Mountain Analysis Station, whitebark pine forests may very well be gone in a century.

That motion may very well be coming quickly; as of late summer season, the USFWS was within the last phases of contemplating the tree for itemizing as Threatened below the Endangered Species Act. A last itemizing choice may very well be introduced this autumn [update: the USFWS officially listed the whitebark pine as Threatened in December 2022], a transfer that may require federal businesses to create complete, proactive restoration plans to make sure that the bushes are round for future generations.

Many ecologists say the itemizing is lengthy overdue.

“Whitebark pine has been a candidate species [for ESA listing] for a very long time,” says Diana Tomback, an ecologist on the College of Colorado Denver. “The itemizing choice is a very long time within the making.”

Tomback is a lead scientist on the Nationwide Whitebark Pine Restoration Plan, a technique for bringing the tree again that was produced by a partnership between the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Basis and the nonprofit conservation group American Forests. The plan attracts from Tomback’s four-decade profession as a scientist learning the connection between whitebarks and nutcrackers.

“The Nationwide Whitebark Pine Restoration Plan depends on the Clark’s Nutcracker to disperse the pine past restored areas,” she says. “The chook is actually the important thing to saving the whitebark.”

However the bond between whitebark and Clark’s Nutcracker is in danger, too. Analysis by Taza Schaming, a wildlife ecologist on the Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative, has discovered that areas with fewer whitebarks additionally had fewer nutcrackers. And fewer nutcrackers means fewer birds to plant the following era of whitebarks.

A Bond Between Chook and Tree

Within the Eighties, Tomback was a grad pupil doing PhD work on the College of California, Santa Barbara. On a mountain climbing journey within the Sierra Nevadas, she was taking a relaxation beneath a whitebark pine tree when she was visited by a Clark’s Nutcracker. After that spark second, she grew to become fascinated with what locals referred to as a “pine crow” and its affinity for whitebarks.

Tomback would go on to conduct groundbreaking analysis that documented how nutcrackers cache a number of thousand whitebark pine seeds in the summertime and autumn—burying caches of wherever from 2 to 10 seeds a couple of centimeters below the soil. Tomback was the primary scientist to point out that it was the nutcrackers that have been dispersing whitebark seeds and serving to the pine unfold. The birds usually cache three to 5 occasions extra seeds than they’ll ever eat, pushed by the organic want to gather and bury when occasions are good. From an evolutionary standpoint, the whitebark pines are relying on the nutcrackers to do that planting. Whitebark pine cones don’t open on their very own, and the seeds don’t have any wings for wind dispersal. As a substitute, the tree produces giant, fatty seeds—with all of the pine cones clustered on the very high of the tree—to draw nutcrackers.

“It appears like a platter of meals when the birds fly over,” says Schaming.

Schaming earned her PhD by way of Cornell College in 2016 whereas operating the longest area examine ever carried out on Clark’s Nutcrackers—a 14-year analysis undertaking on the foraging habits and habitat use of nutcrackers within the Larger Yellowstone Ecosystem [see Soul Mates, Living Bird Autumn 2015]. By monitoring nutcrackers by way of satellite-tracking tags, she revealed that nutcrackers will journey over lengthy distances to search out whitebark pine stands as meals sources and plant seeds throughout a panorama.

“These cones don’t open by themselves. They don’t open from fireplace,” Schaming says. “Their solely technique of dispersal is the Clark’s Nutcracker.”

Blister Rust and Beetles

About 40 years in the past, biologists started noticing that the threads of mutualism between the Clark’s Nutcracker and the whitebark pine have been fraying. Like many five-needle pines—together with limber pines, bristlecones, foxtail, and white pines—whitebarks are prone to blister rust. The illness, attributable to the invasive fungus Cronartium ribicola, had been inflicting issues since its unintended importation within the early 1900s. By the Eighties, Keane started noticing giant outbreaks of blister rust all around the West, with three-quarters or extra of the whitebark pines killed in an outbreak space.

Nutcrackers and Whitebark Pine

Across the identical time, foresters took observe of one other risk—the mountain pine beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae). Although it’s a local pest that hardly ever precipitated main issues to whitebarks (traditionally, the excessive latitudes and elevations favored by these pines meant winter chilly snaps killed many beetles), the hotter winters introduced on by local weather change have tipped the stability within the beetle’s favor. Within the Larger Yellowstone Ecosystem, the mix of pine beetle and blister rust meant that greater than half of all whitebark stands have been lifeless by the early 2010s. Throughout the West, whitebark forests have been worn out in Montana, Wyoming, Oregon, Washington, and Idaho.

The die-off is about greater than only one tree, because the whitebark pine is a keystone species—the pine’s fatty seeds present meals for greater than 100 animal species, together with grizzly bears, crimson squirrels, and Cassin’s Finches. Whitebark pines are additionally the primary tree species to sprout after fireplace and safe the soil whereas performing as nurse bushes for different spruces and firs. And whitebarks play a significant function in offering shade that retains snowpack from melting shortly at excessive elevations, which regulates the circulate of water down into western valleys.

“This tree is the glue that holds the ecosystem collectively,” Keane says. Dropping the whitebark pine, says Keane, would create a ripple impact that might reverberate all through the mountain West. The intimate relationship between whitebark pines and Clark’s Nutcrackers means the die-off amongst bushes may very well be dangerous information for the birds. Though nutcrackers can—and do—eat different meals, it’s arduous to beat the dietary worth of a whitebark pine nut (which ounce for ounce is about calorically equal to Nutella). A chook should eat 20 Douglas-fir seeds to get the identical vitality as a single whitebark seed.

Given the lack of whitebarks, some scientists fear about subsequent declines in Clark’s Nutcrackers. In areas with the most important declines in whitebark numbers, nutcracker numbers have plummeted by nearly 80%.

However it’s arduous for ornithologists to know what’s taking place with the general Clark’s Nutcracker inhabitants throughout their total vary of 11 western states and two provinces, as a result of nutcrackers are an irruptive species—going the place the meals is, completely happy to nest and breed wherever pine cones are loads, and never hesitant to pack up and transfer if meals turns into scarce. Schaming’s work reveals that in years when the whitebark pines produced fewer cones, 71% of the birds she was monitoring left the Larger Yellowstone space, solely to return the following yr.

In Washington State, nonetheless, the birds stayed put when whitebark pine cones have been scarce. Schaming believes that’s as a result of one main distinction.

“They’ve ponderosa pines in Washington. So there’s one other meals supply to maintain them stationary,” she says.

Schaming has additionally discovered that even a couple of cone-bearing whitebark pines, even just a few bedraggled holdouts, can hold Clark’s Nutcrackers on the panorama. So long as the birds have a big space to name house and at the very least some whitebarks— together with Douglas-firs or different pines as different meals sources—they need to stay within the space, in keeping with a 2020 examine by Schaming that was printed in PLOS ONE.

And maintaining nutcrackers on the panorama is the important thing to bringing again the whitebark pine. As a result of if the birds disappear, “that’s going to make it tougher for the bushes to come back again. It’s a suggestions loop,” says Chris Ray, a analysis ecologist with The Institute for Chook Populations. “With a view to make it possible for the pine can regrow, we have to hold the nutcracker round, too.”

For Whitebark Restoration, the Chook Is Key

Schaming, Tomback, and plenty of different scientists have been pushing the USFWS for a number of years to offer Endangered Species Act safety to whitebark pines. Now they are saying the restoration plan must roll out quick—as a result of whitebark numbers are diminishing shortly, and time will not be on their aspect.

“It takes a very very long time for a 700-year-old tree to get replaced,” says Nancy Bockino, a biologist with Grand Teton Nationwide Park and a mountain information. “It’s determined that we do one thing now.”

The U.S. Forest Service has began breeding whitebark pines which are immune to blister rust; these seedlings could be planted in areas which have misplaced essentially the most bushes. However any human efforts to replant total mountainsides of disease-resistant whitebark pines might be dwarfed by the Clark’s Nutcracker— which may cache as much as 100,000 seeds in a single yr, and do it free of charge. Tomback estimates that nutcrackers present an ecosystem service that equates to $2,500 per hectare, the equal value of U.S. Forest Service seeding. With labor shortages hitting the Forest Service like in every single place else, the company could not have the required assets for enormous replanting efforts.

To facilitate free labor by nutcrackers, the Nationwide Whitebark Pine Restoration Plan recommends the creation of so-called “nutcracker openings,” or cleared areas with numerous room for nutcrackers to cache their favourite seeds.

In line with Tomback, the dispersal of these specifically bred blister-rust-resistant pines throughout landscapes—and full restoration for the whitebark—will relaxation squarely on the feathered shoulders of the Clark’s Nutcracker.

“No different tree will depend on an animal so intimately,” Tomback says.

Correction: An earlier model of this story incorrectly referred to ponderosa pine as one of many five-needled pine species which are prone to blister rust illness. The sentence ought to have included white pine, not the three-needled ponderosa pine. The sentence has been corrected.

Carrie Arnold is a contract science author whose work has appeared within the Washington Submit, Scientific American, Audubon, and Slate.

[ad_2]